NO EASY FIX

Study suggests equal insurance coverage may not level lung cancer disparities

A new study by researchers at East Carolina University suggests that equivalent health insurance coverage may not level the disparities between African-American and Caucasian lung cancer patients when it comes to the stage at which they’re diagnosed.

Over the course of two years, researchers at the Brody School of Medicine’s Center for Health Disparities and the Leo W. Jenkins Cancer Center examined the medical records of 717 black and 1,634 white lung cancer patients who were treated at the cancer center between 2001 and 2010. They found that – after adjusting for age, sex and smoking history – blacks had at least a 14 percent greater risk of being diagnosed with a more advanced stage of lung cancer than whites for all insurance types other than Medicaid.

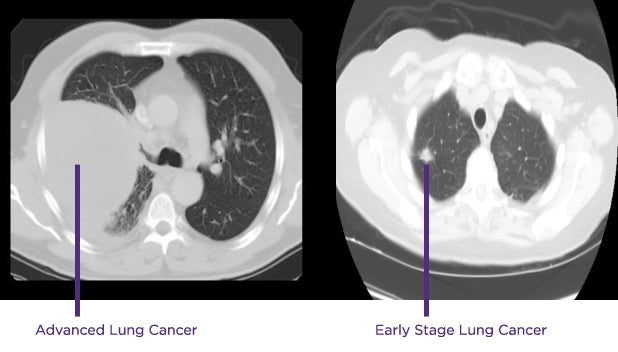

Two lung CT scans shown above illustrate the significant difference between advanced-stage lung cancer and cancer detected early. (Contributed image)

“For years we’ve known that African-Americans typically present with a later stage of lung cancer than Caucasians,” said ECU epidemiologist Dr. Jimmy Efird, assistant director for the Center for Health Disparities and lead author of the study.

“The thought was that these disparities could be attributed to differences in health insurance coverage because African-Americans are more likely to be underinsured or not insured at all,” he said. “But our study looks at how African-Americans do within each type of insurance, and the results demonstrate that this result persists even when they have the same coverage.”

Lung cancer is by far the leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States, responsible for nearly 160,000 deaths a year, according to the American Cancer Society. While the general population has experienced a decline in lung cancer mortality in recent years, rates remain disproportionately high among racial minorities, presumably because they aren’t likely to be diagnosed until the disease is more advanced.

Efird said the study implies there is no easy fix. He said further research is needed to identify the causes behind the racial disparities, but he believes multiple historical factors are involved.

“We need to dig deeper,” he said. “We know that African-Americans are more likely to place a lower priority on health care, to mistrust health care providers, to delay treatment.

“We need to explore these issues along with others that are probably contributing simultaneously to the problem, like socioeconomic status, residential segregation, education levels, access to services, genetics, behaviors, occupational exposures,” Efird said. “This is a very gray area. It’s complex.”

In early February 2015 the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced that Medicare, the federal health insurance plan for people over age 65, would begin paying for annual, low-dose CT scans to look for early evidence of lung cancer in people considered at highest risk: those aged 55 to 77 who are either current smokers or have quit smoking within the last 15 years, who have a tobacco-smoking history of at least an average of one pack a day for 30 years, and who get a written order from a doctor.

Efird and his colleagues would like to see African-Americans also targeted for coverage in the near future. In the meantime, Dr. Mark Bowling, director of interventional pulmonology for ECU, hopes the study will increase awareness of the disease, encourage people to seek attention earlier and pave the way for screening opportunities for more people.

“Lung cancer screening is going to change the history of lung cancer,” he said. “We’re witnessing history in the making. Now that Medicare has picked it up, other insurances will follow.

“We can defeat lung cancer,” he added. “It is very curable, especially when it’s found early.”

Co-authors of the study include Dr. Hope Landrine, director of the Center for Health Disparities; ECU graduate student Kristin Shiue; Brody graduate Dr. Wesley J. O’Neal and visiting radiation oncologist Julian Rosenman.

The Leo W. Jenkins Cancer Center, which funded the study, is a joint venture between the Brody School of Medicine and Vidant Medical Center. It serves all of rural eastern North Carolina, where there is a high incidence of lung cancer, and where lung cancer mortality rates are consistently higher among blacks than whites. Of the 29 counties in the region, 97 percent fall below the national per capita income, and 90 percent have a higher percentage of African-Americans than the national average, according to a 2010 U.S. Census Bureau report.

The study was published in the online journal SpringerPlus. The entire report can be found at http://www.springerplus.com/content/3/1/710.