JOINT EFFORT

ECU researchers receive funding to study arthritis treatment

Researchers at East Carolina University’s Brody School of Medicine have earned funding that could lead to pain relief and improved mobility for millions of people who suffer from osteoarthritis.

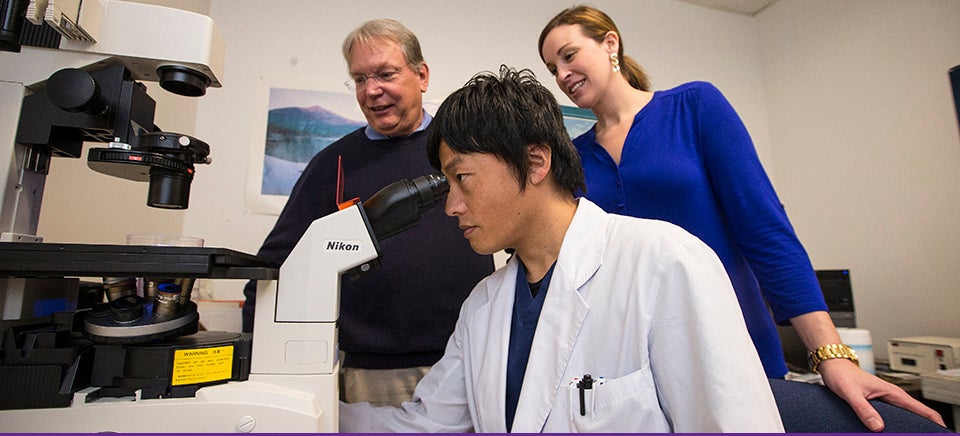

Dr. Warren Knudson, professor in the Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology; Dr. Cheryl Knudson, professor and chair of the department; Dr. Emily Askew, research assistant professor; and Dr. Shinya Ishizuka, post-doctoral scholar, recently received a two-year, $356,950 grant from the National Institute for Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases – a division of the National Institutes of Health.

The grant will fund research focused on a potential treatment for degenerative osteoarthritis, a chronic condition in which cartilage – the material that cushions joints – breaks down. Its deterioration allows the bones to rub against each other, resulting in pain, swelling and loss of movement. The disease most often affects the fingers, hips, knees and lower backs of aging adults or adults who have experienced joint injuries.

“There’s no cure for osteoarthritis, or even a way to slow it down,” said Warren Knudson. “The tissue just keeps progressively wearing away to the underlying bone, which can be very painful. Right now, all we can do is treat the symptoms. It’s a real quality of life issue.

“And everyone gets arthritis if they live long enough,” he added.

According to the Arthritis Foundation, osteoarthritis affects about 27 million Americans and costs the economy dearly in direct medical care and lost workdays.

The issue, according to Knudson, is that unlike other types of tissue in the body, cartilage lacks the ability to regenerate, and with age, loses its ability to repair itself.

Many people who suffer from osteoarthritis eventually resort to total joint replacement, an invasive procedure usually followed by a lengthy healing process and extensive rehabilitation.

Others attempt to manage their symptoms with dietary supplements like glucosamine or chondroitin sulfate, even though they haven’t been proven to offer much relief. “Because cartilage is largely made up of chondroitin, people think that taking chondroitin sulfate will replace their cartilage,” Knudson said, “but that’s not true.”

Some physicians inject affected joints with hyaluronic acid, a relative of chondroitin sulfate that comprises most of the lubricant naturally found in joints. “These injections do seem to make people feel better for a time,” Knudson said.

But what if cartilage could be influenced to repair itself?

Building on his decades of research into the biochemistry of hyaluronic acid, Knudson and his team are trying to answer that question.

One project their lab has undertaken is cloning the gene that makes hyaluronic acid, engineering that gene into a virus, injecting the virus into small disks of human or bovine cartilage (from cow hooves) and growing the disks in vitro.

“We’re basically trying to replace what we think is a defective critical gene with a better one and see how it will express itself,” Knudson said. “We want to see if the deteriorated cartilage can rescue itself – if it can regain the structural properties of pliancy and strength that we see with the original cartilage.”

In a second version of that experiment – which mimics the autologous cartilage transplants many younger people require after joint injury – they’re drilling a hole in the cartilage and injecting genetically altered cells back into the hole to see if the tissue will repair itself.

Thus far, Knudson’s team has discovered that their “modified” cartilage begins making its own hyaluronic acid in increasing amounts. “Is this beneficial?” Knudson said. “Well, that’s what we’re trying to find out.”