Jenkins honored by UNC Board of Governors

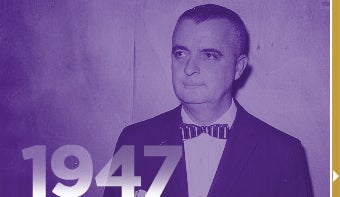

Then-president John Messick hires 34-year-old Leo Warren Jenkins as dean of East Carolina Teachers College. Jenkins previously held a position in the New Jersey state educational administration. He served in the role of dean until his appointment as vice president of East Carolina College in 1955.

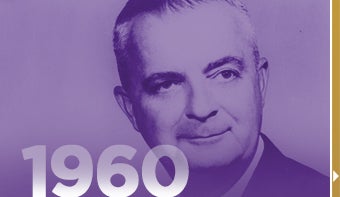

Jenkins is named president of East Carolina College, receiving overwhelming support from the campus community. He immediately makes it clear that growth of the college is his priority. In his inauguration speech, Jenkins pledges to the state that “I will do my best to sustain and extend the responsibility which East Carolina has to contribute to the enrichment and well-being of our state.”

Early in Jenkins’ presidency, East Carolina hosts then-Senator John F. Kennedy, who visited the college as part of his presidential campaign trail.

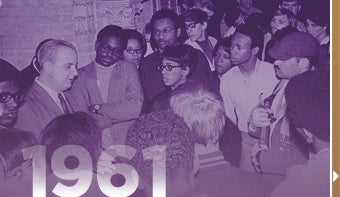

Shortly after becoming president of the college, Jenkins manages to avoid legal and social conflict during a time of high racial tension. In 1961, he ushers in the era of integration by encouraging a nonracial admissions policy and admitting several African-American teachers pursuing recertification. Jenkins’ subtle and diplomatic approach lessens racial tension on campus and avoids a court-ordered integration.

Under Jenkins’ leadership and advocacy, East Carolina becomes a regional university in 1967 and joins the University of North Carolina system in 1972. Since then, ECU has grown to become an emerging research institution, a pioneer of medical innovation and the third-largest public university in North Carolina.

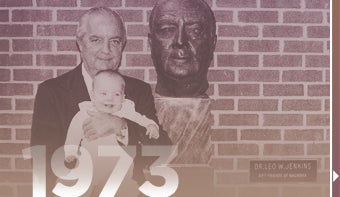

During his tenure, Jenkins supports art, music, literature and culture at East Carolina University, instituting an artist-in-residence program for the already rapidly growing School of Art. In 1973, the university began constructing the Jenkins Fine Arts Center, and began hosting classes even before its completion in 1977.

Jenkins displays an editorial cartoon criticising the concept of a medical school at East Carolina. Jenkins was widely lampooned in numerous derogatory cartoons from newspapers across the state for his “populist” agenda. Regardless, in 1974, the North Carolina General Assembly appropriates the funds to establish what would become the East Carolina University School of Medicine.

Jenkins congratulates Coach Dye and the Pirate football team on their 1976 Southern Conference Championship. Jenkins’ fervent support of East Carolina University’s athletics program came during a time of its vast expansion, including the construction of Dowdy-Ficklen Stadium and the introduction of women’s athletics.

Chancellor Emeritus Jenkins receives the first honorary doctorate awarded by East Carolina University at its 1983 commencement. According to author Mary Jo Jackson Bratton, a citation accompanying the doctor of letters degree deems Jenkins “a great leader and principal architect for progress during East Carolina University’s most dynamic period of growth.”

The Radiation Therapy Center is constructed in 1984. A second floor is added shortly thereafter, and it is redubbed the Leo W. Jenkins Cancer Center. Behind the center stands the Brody Building, a state-of-the-art facility built to house East Carolina’s rapidly-growing School of Medicine only a few years after the enrollment of its first class. Jenkins’ leadership led to a surge of growth for ECU, with many new buildings being constructed on campus.

Jenkins’ record of service to higher education is honored in 2014 with the Board of Governors’ prestigious University Award. His dedication to the university and community embodied the spirit of East Carolina’s motto, Servire, to serve. The waves made by Jenkins created a ripple effect, prompting an age of growth and success that East Carolina continues to experience today. “His legacy stands tall in that he was a champion for East Carolina … and of course the burgeoning East Carolina School of Medicine,” says Paul Cunningham, dean of the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University.

Then-president John Messick hires 34-year-old Leo Warren Jenkins as dean of East Carolina Teachers College. Jenkins previously held a position in the New Jersey state educational administration. He served in the role of dean until his appointment as vice president of East Carolina College in 1955.

Jenkins is named president of East Carolina College, receiving overwhelming support from the campus community. He immediately makes it clear that growth of the college is his priority. In his inauguration speech, Jenkins pledges to the state that “I will do my best to sustain and extend the responsibility which East Carolina has to contribute to the enrichment and well-being of our state.”

Early in Jenkins’ presidency, East Carolina hosts then-Senator John F. Kennedy, who visited the college as part of his presidential campaign trail.

Shortly after becoming president of the college, Jenkins manages to avoid legal and social conflict during a time of high racial tension. In 1961, he ushers in the era of integration by encouraging a nonracial admissions policy and admitting several African-American teachers pursuing recertification. Jenkins’ subtle and diplomatic approach lessens racial tension on campus and avoids a court-ordered integration.

Under Jenkins’ leadership and advocacy, East Carolina becomes a regional university in 1967 and joins the University of North Carolina system in 1972. Since then, ECU has grown to become an emerging research institution, a pioneer of medical innovation and the third-largest public university in North Carolina.

During his tenure, Jenkins supports art, music, literature and culture at East Carolina University, instituting an artist-in-residence program for the already rapidly growing School of Art. In 1973, the university began constructing the Jenkins Fine Arts Center, and began hosting classes even before its completion in 1977.

Jenkins displays an editorial cartoon criticising the concept of a medical school at East Carolina. Jenkins was widely lampooned in numerous derogatory cartoons from newspapers across the state for his “populist” agenda. Regardless, in 1974, the North Carolina General Assembly appropriates the funds to establish what would become the East Carolina University School of Medicine.

Jenkins congratulates Coach Dye and the Pirate football team on their 1976 Southern Conference Championship. Jenkins’ fervent support of East Carolina University’s athletics program came during a time of its vast expansion, including the construction of Dowdy-Ficklen Stadium and the introduction of women’s athletics.

Chancellor Emeritus Jenkins receives the first honorary doctorate awarded by East Carolina University at its 1983 commencement. According to author Mary Jo Jackson Bratton, a citation accompanying the doctor of letters degree deems Jenkins “a great leader and principal architect for progress during East Carolina University’s most dynamic period of growth.”

The Radiation Therapy Center is constructed in 1984. A second floor is added shortly thereafter, and it is redubbed the Leo W. Jenkins Cancer Center. Behind the center stands the Brody Building, a state-of-the-art facility built to house East Carolina’s rapidly-growing School of Medicine only a few years after the enrollment of its first class. Jenkins’ leadership led to a surge of growth for ECU, with many new buildings being constructed on campus.

Jenkins’ record of service to higher education is honored in 2014 with the Board of Governors’ prestigious University Award. His dedication to the university and community embodied the spirit of East Carolina’s motto, Servire, to serve. The waves made by Jenkins created a ripple effect, prompting an age of growth and success that East Carolina continues to experience today. “His legacy stands tall in that he was a champion for East Carolina … and of course the burgeoning East Carolina School of Medicine,” says Paul Cunningham, dean of the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University.

CHAPEL HILL–Leo W. Jenkins would not look upon his latest triumph as a personal gain–instead, it would be a victory for East Carolina University and its region.

Jenkins was posthumously honored Thursday, April 10, with the University Award, the highest accolade given by the University of North Carolina Board of Governors for distinguished service to higher education. Jenkins’ son, N.C. Special Superior Court Judge Jack W. Jenkins, accepted the medallion on behalf of his siblings who took the stage with him to a standing ovation.

Jenkins expressed pride in his father’s achievements and the impact he had on statewide higher education and quality of life.

“As his son, as a proud graduate of East Carolina University, as a career public servant striving to live up to my father’s legacy, and as a lifelong Down East resident, I do in fact walk taller, as do all eastern Carolinians because of Leo Warren Jenkins,” he said. “I’m certain my father would be deeply moved” by this honor.

The atmosphere in the George Watts Hill Alumni Center in Chapel Hill was reverent as the highlights of Jenkins’ legacy were summarized in a UNC-TV video, which played to the more than 275 guests.

UNC President Tom Ross said that Jenkins “dared and prodded eastern North Carolina to dream big.” He added, “He helped instill in the region a sense of pride and can-do spirit that never waned.”

ECU Chancellor Steve Ballard detailed how Jenkins’ work has affected not only the growth in academic programs at the school but the leaders who have steered the university since Jenkins retired in 1978.

“He was a transformational leader. Leo Jenkins was a giant whose legacy lives on in dozens of ways…. The only negative that I can think of about Dr. Jenkins is that all chancellors who have succeeded him live in his shadow,” said Ballard.

“It is rare during our board meetings that I’m not asked, how would Leo have handled this,” Ballard continued. “I often wish I could have asked him.”

Also honored was Thomas S. Kenan III, a tireless advocate for education, the arts and history in North Carolina. A graduate of UNC-Chapel Hill, Kenan has been a devoted volunteer and benefactor to many institutions of higher education in the state, including several UNC campuses.

The Change-Maker

Jenkins stood at the helm during some of East Carolina’s most bustling, productive years in the 1960s and ’70s. There was an air of promise on campus, a sense of hope for a greater presence in the East. Jenkins rallied campus and community to focus on expanding the reach and impact of what was then East Carolina College.

By the time the dust settled, Jenkins was credited with changing the face of ECU and spurring a chain reaction across the state as other colleges began realizing their potential. Among countless accomplishments, Jenkins guided the college into official university status, fought for a medical school in Greenville and oversaw expansion of academic, medical and athletic facilities. He also was instrumental in integrating campus without a court order, boosted support for creative and performing arts and pursued changes on campus that reverberated from the student body to citizens across the East.

“With his sense of selfless devotion, Leo Jenkins established a gold standard that we continue to honor and stand in awe of,” said Dr. John Tucker, ECU professor of history and university historian, “and we continue to emulate that to the best of our ability.”

Named dean of East Carolina College in 1947 by then-chancellor John Messick, Jenkins first turned heads because of his New Jersey roots and accent. It didn’t take long for his character to win over the campus and community, and he was named vice president in 1955. With a background as a Marine Corps officer as well as an education that included a master’s degree from Columbia University and a doctorate of education from New York University, Jenkins was worldly and brought a fresh perspective to ECC leadership.

By the time he was named president of ECC in 1960, Jenkins had a solid support system in place in the East. His belief in the potential of ECC was infectious, and he rallied students, faculty and community members to expect more from the growing college. Then he took that campaign statewide.

His push for a medical school was met with skepticism by state politicians as well as leaders of other universities, who saw a medical school in Greenville as a threat to their funding and resources.

“He was a thorn in the side of the rest of the state,” said David Whichard, former editor of The Daily Reflector and family friend of Jenkins. “He had the character of both a ne’er do well and a hero, and he did both well.”

His campaign for university status for ECC also threatened to rock the state’s higher-education system that centered around one university and smaller colleges across the state. When ECC became East Carolina University in 1967, the campus and region could more easily picture how the institution could bring economic productivity, better health care and cultural growth.

“He saw the potential in eastern North Carolina and this institution,” Whichard said, “not what we could build today, but what comes tomorrow.”

Causing A Stir

Worn, yellowed newspaper pages from years long gone are testaments to the tumult caused by Jenkins during those formative years. Editorials decried his efforts to take East Carolina to new heights, and political cartoons depicted him as a menace looking to shake the foundation of higher education in the state.

Leaders in state government and higher education urged Jenkins to back down, saying it was not the right time for East Carolina to expand its mission.

“It’s not an easy life to be challenged repeatedly by other people,” said Jim Bearden, who holds the longest continuous tenure as a professor at ECU and witnessed the campus growth during Jenkins’ tenure, “and his was a lonely role in that regard, but he carried it well.”

Jenkins took the cartoons and criticism in stride, using them as a catalyst for his vision. His notoriety also meant that people across the state caught wind of what the quickly growing college was moving toward. “He really could let whatever criticism came his way fall right off his shoulders,” Bearden said.

Jenkins also had an instinct for handling issues that had the potential to shake the university’s foundation. He implemented integration gradually, so that it naturally occurred over time before government mandate.

“He accomplished desegregation without a court order,” said Ballard, “and he did it because he thought it was the right thing to do.”

‘A Hero to All’

Many stories passed down over the years on campus and in the community ensure that Jenkins’ vision thrives today.

“People still tell Leo Jenkins stories,” Ballard said. “Leo is still very much alive for all of the Pirate Nation.”

Jenkins’ background in the military and academia opened his mind to a world of perspectives and experiences. He championed the arts and athletics, enjoyed painting and was a founding member of St. James United Methodist Church. His wide range of interests invited opportunities to interact with a broad range of people.

“He was a man whom in the end was all but impossible not to like,” Tucker said. “He was able to relate to people and draw out the best in them. People wanted to be involved in the world Leo Jenkins was a part of.”

Even the students became enamored with Jenkins. During years of unrest in the ’60s, students protested issues from the failed state bond referendum that would have allowed East Carolina to update residence halls, to overnight co-ed visitation and the Vietnam War.

According to Mary Jo Jackson Bratton’s book “East Carolina University: The Formative Years, 1907-1982,” Jenkins on one occasion stood atop a police car during a protest over the failed bond referendum and implored a mob of students to return peacefully to campus. He led the way on foot, and again addressed the group’s concerns in front of the Austin Building.

Jack Jenkins remembers accompanying his father on routine evening walks around campus, when his father would stop to talk to passersby, including visitors, students and faculty. While Leo Jenkins loved meeting new people, he pursued those conversations first and foremost to keep his ear to the ground on the campus climate.

“He would hear of things–some good and some bad–and take action accordingly,” Jack Jenkins said. “For instance, a student might mention, in passing, a really interesting class. Daddy would figure out the professor’s name and send her a positive note.”

Jenkins’ spirit sparked a renewed energy not only in Greenville but also in communities in the East that stood to benefit from a stronger East Carolina institution. “He was one of the greatest things to happen to eastern North Carolina,” Whichard said. “He was a great hero to all of us.”

Proof Positive

Following East Carolina’s victory of university status, the Raleigh News and Observer’s next-day editorial was headlined “Now Prove It,” and still dripped skepticism over ECU’s future, according to Bratton’s history.

“The foundation he created has allowed numerous people and faces to really move this university forward,” Ballard said.

Jack Jenkins said his father would consider the University Award the result of countless supporters’ efforts to see ECU serve the region and state to its highest potential. “My dad would not take any personal credit, but rather would accept this on behalf of the Pirate Nation,” he said. “It’s nice to be recognized, but he knew that East Carolina’s success was a team effort, and that team includes generations of true Pirates everywhere.”

“He was not the kind of man who was looking to leave a monument or have his name on buildings,” Tucker said. “He didn’t expect to be recognized; he didn’t do it for the glory.”

Despite his expectations, Jenkins’ name adorns campus and community buildings, including the Jenkins Fine Arts Center and the Leo W. Jenkins Cancer Center.

Although Jenkins passed away in 1989, the reverberations of his achievements are still being measured today.

“It’s only at this point that people are beginning to fully realize in ways that can’t be denied the truly incredible legacy that Leo Jenkins left ECU, the campus, region, state and nation,” Tucker said. “Now it’s clear. Whatever happens next, our record is officially solid.”

UNC-TV will air the Leo W. Jenkins tribute video during “N.C. Now” at 7:30 p.m. Monday, April 14.

— Jeannine Manning Hutson contributed to this article.

Photos and Leo Jenkins news video by Cliff Hollis. Event video by Bryan Edge.

Design by Mike Litwin