A CLOSE CALL

Hero of 'The Goldsboro Broken Arrow' speaks at ECU

Jack ReVelle knows how close Wayne County and much of eastern North Carolina came to being transformed by a mushroom cloud into a radioactive wasteland.

“It was damn close,” he told an audience of about 140 students, faculty and locals at East Carolina University on Monday.

ReVelle was the young Air Force weapons disposal specialist who, in January 1961, was charged with disarming two nuclear bombs that plummeted from a crippled B-52 into a Wayne County tobacco field about 20 miles southwest of Greenville.

It was the height of the Cold War, and the Statofortress carrying the bombs was on a Strategic Air Command mission over the Atlantic Ocean. The huge bomber developed mechanical problems and was attempting to return to Seymour Johnson Air Force Base.

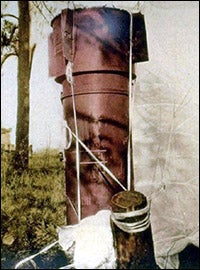

A 1961 image shows one of the bombs that escaped during the crash. (Contributed photo)

The plane broke up while still several thousand feet in the air. Its eight-man crew bailed out just as the tail broke off and dislodged two MK-39 bombs from their storage racks in the bomb bay. Each weighed 6,700 pounds and packed 250 times the explosive power of the blast that destroyed Hiroshima.

ReVelle, who holds degrees in both chemical and industrial engineering, was immediately summoned from his base in Ohio, where he was in charge of ordnance disposal.

“When I got to the site, we found the parachute had deployed on one bomb,” ReVelle said at the campus event. “The parachute caught in a tree, and the bomb was intact and standing upright. When I checked it I found the arm/safe switch was still in the safe position, so it had not begun the arming process.”

That was not the case with the second bomb. Its parachute failed to open and it struck the ground at about 700 miles per hour, ReVelle said.

ReVelle and his crew began digging to recover the second bomb. After five days, they found parts of the bomb and the crucial arm/safe switch. “Until my death I will never forget hearing my sergeant say, ‘Lieutenant, we found the arm/safe switch,’” ReVelle said. “And I said, ‘Great.’ He said, ‘Not great. It’s on arm.”

Later tests determined the second bomb had gone through five of six steps toward detonation, ReVelle said.

Had that bomb exploded, “it would have created a crater eight football fields wide. It would have destroyed every structure within a four-mile radius. There would have been a 100-percent kill zone for eight and a half miles in every direction.” A lethal cloud of radiation would have blanketed the entire region, he said.

“We’ll never know with any precision exactly how close we came to the worst catastrophe imaginable,” ReVelle said. “But it was damn close.”

Although the bomb had not detonated, it remained a radioactive menace. Especially worrisome to ReVelle was the uranium and plutonium core that provided the fissionable material for the atomic reaction. Some called that part of the bomb the “Demon Core,” ReVelle said. He called it “the pit.”

On the fifth day of the dig, ReVelle – not wearing any protective clothing other than a pair of gloves – descended a ladder into the muddy hole where the second bomb fell. Reaching the bottom, he said he fished around in the muddy water and felt something. It was round, about the size of a volleyball. It was the pit.

“It was pretty heavy. As I carried it up out of that hole, I remember thinking, ‘Don’t drop it.’”

Today, ReVelle is retired and lives in southern California. A book commemorating the 50th anniversary of the near-disaster, “The Goldsboro Broken Arrow,” came out two years ago. The author, former Strategic Air Command officer Joel A. Dobson of Greensboro, also attended ReVelle’s lecture.

Dobson and ReVelle pointed out that East Carolina has a stronger connection to the event than the short distance to the site would suggest. One of the pilots of the B-52 was First Lt. Adam Mattocks, a North Carolina A&T State University graduate. One of the bombs zoomed past him as he parachuted to safety.

Mattocks had three children, all of whom attended ECU.

“I think the interest from the Department of Engineering was to share an example from history of how an industrial engineer contributed to the betterment of society,” said Evelyn Brown, professor in ECU’s Department of Engineering. “Even though you do not have to be an IE to be on a bomb disposal unit, it is interesting that Dr. ReVelle is an IE with this part of history to his credit.”

“We asked the College of Business to help us sponsor Dr. ReVelle’s visit since a lot of what they teach in their operations management curriculum relates to what industrial engineers do.”

The ECU Office of Military Programs also sponsored the event.

A photograph taken at the scene of the 1961 crash shows a team attempting to dismantle the nuclear bomb. (Contributed photo)