PIRATE READ:

Son brings story of Henrietta Lacks to life

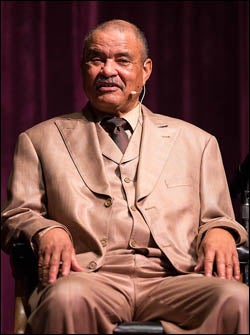

Whenever anyone mentions David “Sonny” Lacks’ mother, Henrietta, a small, private smile crosses his lips before he lifts his eyes and speaks. When he begins to talk about her, it’s in a reverent whisper, but his voice grows stronger as he launches into the story of Henrietta Lacks, her death and the ensuing tale of ethics, race and science that revolutionized modern medicine.

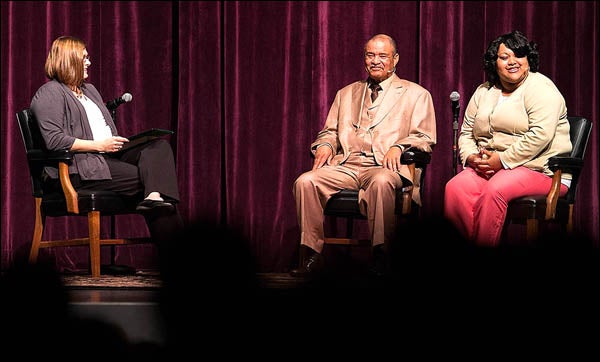

David Lacks

Lacks spoke to a packed crowd Nov. 12 in Wright Auditorium about the 2012 East Carolina University Pirate Summer Read selection, “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” by Rebecca Skloot. Students and community members listened as David Lacks and Henrietta Lacks’ great-granddaughter Veronica Spencer told the story of how, after Henrietta was diagnosed with cervical cancer in 1951, a tissue sample was taken without her knowledge or permission.

The cells never died.

Over the years, Henrietta’s cells have become an immortal source of cells for research that has found breakthroughs in treatment and diagnosis of disease, assisted in human gene mapping and in-vitro fertilization research and altered the course of medicine as it is today. Known as HeLa cells, they helped develop the polio vaccine and have increased medical professionals’ understanding of cancer, AIDS and numerous viruses. HeLa is the most widely used cell line in the world used for biomedical research.

“It’s such a legacy that the HeLa cells came from Henrietta Lacks, a poor, black farmer woman,” David Lacks said. “Anyone in the world would feel real good about a member of their family contributing to the world. I think she would be glad because it helps so many.”

It took more than 20 years for the Lacks family to find out that cells shaved off a tumor from their matriarch were now making a difference in research—and lives—all over the world. Today, members of the close-knit family are torn between being at peace with what was taken from Henrietta Lacks without permission and feeling frustrated that while the sharing of her cells—first taken at Johns Hopkins Hospital—has boomed into a nearly $3 billion industry, her descendants struggle to cover their own medical bills. Some of them still today harbor fear and general mistrust toward the medical field.

“The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” was chosen as this year’s Pirate Summer Read selection because it lends itself to students’ awareness of social issues including medical ethics, race, family culture, science and true-life accounts in literature. After Skloot spent 10 years researching and writing the story—with much help from Henrietta’s daughter Deborah—the book hit the New York Times bestseller list in 2010.

The book was one of five finalists for the Pirate Summer Read selection, and the committee chose it because “the book had some really valuable social issues,” MaryBeth Corbin, co-chair of the ECU Pirate Read committee. “(The committee) felt students could relate to this book more than some of the others.”

Before Monday night’s presentation, Lacks and Spencer visited several classes on campus and had the chance to answer students’ questions. The two enjoy touring college campuses all over the country because of students’ genuine interest in the family’s journey from privacy to tragedy to legacy, said Spencer.

“There’s such school spirit,” Spencer said, “and everywhere you go, students think outside the box. They accept you, bring you in and embrace you.”

Students were also eager to hear straight from Henrietta Lacks’ family. During the presentation, students from a wide variety of colleges and disciplines asked questions about family members, their opinions on the book and their thoughts on the lack of compensation—or apology—from Johns Hopkins.

Veronica Spencer

“I think the family has been compensated as far as knowing what her cells have done,” David Lacks said. “We would like to have been compensated (financially), but it’s a thin line to find out how to go about getting anything from what they’ve done so far.”

Some younger members of the Lacks family see it differently. Veronica Spencer said some of her relatives carry with them a fear of the financial burdens of receiving medical care. They feel they should have received a settlement.

These days, family members attend doctor’s appointments in pairs, making sure the patient fully understands diagnoses, treatment options and costs. “We were already a close-knit family,” Spencer said, “but this taught us to be closer and look out for one another.”

They also look out for Henrietta by educating others on who she was—a wife, mother, grandmother, sister, daughter and cousin—beyond the identity as only a group of cells that never died. “She’s not just the cells, she’s a person,” Spencer said.

David Lacks said the book does a good job of conveying Henrietta as a vibrant wife and mother who opened her home and her kitchen to weary family members and who loved to go out dancing with her girlfriends.

The book follows Henrietta’s own discovery that something was not right with her body, her ordeal at Johns Hopkins through treatments that left her torso charred from radiation and her final agonizing hours during which she made sure her children would be looked after by their father and other relatives.

Reading the book helped Spencer understand the great-grandmother she never met and relate to other members of the family, but it’s also a very personal account of a very private family.

“It opens up old wounds,” she said. “It opens up a chapter you thought was closed.”

David Lacks’ sister Deborah was persistent in facing those wounds, even when the rest of the family was reluctant to let Skloot interview them for the book. Deborah wanted answers about her mother, the cells and the extent of their influence on society. She, like Skloot, thought the world should know the woman behind the faceless cells.

Lacks and Spencer brought that woman to life for the audience Monday, telling stories peppered with funny details that caused ripples of laughter throughout the auditorium.

“It’s definitely an honor to be a part of her family,” Spencer said. “[The book] doesn’t lessen the blow of having her cells taken from her, but a part of her is alive and that’s amazing.”