PART SCIENCE, PART ART

ECU graduate drives Curiosity rover on Mars

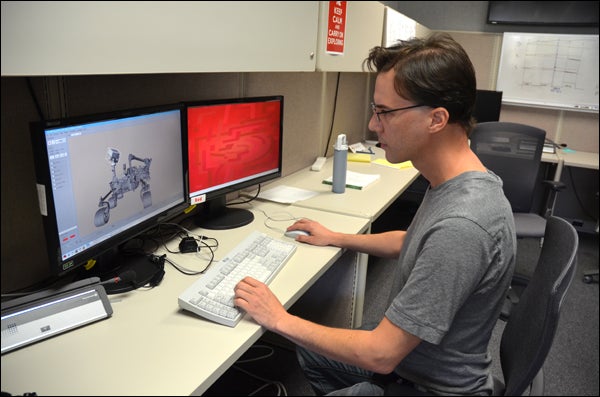

ECU graduate Scott Maxwell, who is on the team to drive the Mars rover Curiosity, is shown at work at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The sign on his wall states, “Keep calm and carry on exploring.” (Photo courtesy of Scott Maxwell)

Scott Maxwell describes his job as being a chauffeur for science but he wants people to know that he does not use a joystick to drive the Mars Curiosity rover, NASA’s $2.6 billion, SUV-sized nuclear-powered machine that’s just beginning to explore the red planet.

“At their closest points, it takes eight minutes for a signal to get to the rover and back to me,” Maxwell explained. “When Earth and Mars are at their furthest distance, it takes 40 minutes to hear back. Try backing your car out of the garage using that data.”

The 1992 East Carolina University graduate, whose title is Mars Rover Team Lead, is among the most experienced of about a dozen engineers who are entrusted with driving the NASA rovers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. He’s worked for JPL for 18 years and was on the original team driving the Spirit and Opportunity rovers after they landed in 2004. Although it had a life expectancy of 90 days, Opportunity continues to function effectively, Maxwell said.

The Curiosity rover transmitted images from the surface of Mars like the one above. (NASA photo)

“There are times when I drive two rovers in one sol,” Maxwell said, using the term for a Martian day. “Curiosity is rated for two years, so we’re pretty sure that we can get at least that much science out of it. I’ve been driving these rovers for nearly nine years, so with Curiosity I’m hopeful that I still have a long career ahead.”

Maxwell, 41, apologized for being a little groggy for this interview. On a previous night his team drove Curiosity about 100 feet, its longest trek to date, and it was a nail biter. He works nights on an ever-changing clock because a Mars sol is about 37 minutes longer than an Earth day.

“I have this really neat watch that I always have on me because it has Mars time on one side and Earth time on the other. So, this is sol 30 in terms of the mission and I’ve just finished a long day,” he said.

“We are just starting the last part of our commissioning phase where we are checking out the rover to be sure it has all its fingers and toes. Next we will go to NASA and make a presentation to the effect that the rover is in good shape, it’s all checked out and they need to give us free rein to drive it,” he said.

After Curiosity’s successful landing on Aug. 6, President Barack Obama telephoned Maxwell’s JPL group to offer congratulations. Maxwell said, “There are not really too many things that you do in your life when the president of the United States will call you and congratulate you. I’ve been lucky enough to experience that twice. I was here when Bush called in 2004 after Spirit landed.”

He explained that driving a rover is part science, part art. “The last thing the rover does before shutting down at night is it looks all around and takes pictures of its surroundings and then transmits that to us. We reconstruct that landscape on our computers, in 3-D, and use animations—which is the art part–to find the safest path to get it where it needs to go,” Maxwell said.

“By the time the rover wakes up, the new programs already are written, they’ve been uploaded and it takes off. And then we come back to work 12 hours later to find out if we’ve scraped the fender on the side of the garage.”

Maxwell said he was bitten by the science bug as a kid growing up in Rocky Mount. At first he was afraid to dream big. “Coming from an economically depressed area in rural eastern North Carolina, I always felt like there was this wall of glass between me and my future. I had it in the back of my mind that it wouldn’t work out for me. But you know, that’s just an illusion. You absolutely can do anything in the world (because) all those walls that you think are there, they aren’t.”

He paused, and then corrected himself. “You can do anything in the world if you work hard enough.”

As an ECU student, Maxwell double majored in English and computer science. He said he usually kept three part-time jobs – as the tech support person for the Joyner Library computer room, as the tech support person for The East Carolinian newspaper, and as a science fiction and technology columnist for TEC.

Then, just as he was about to graduate, he learned he had cancer. He was diagnosed with stage 2 Hodgkin’s lymphoma by a doctor at the Brody School of Medicine and received weeks of radiation therapy at Pitt County Memorial Hospital. “Fortunately for me, everybody did their job really well because I just marked 20 years of being cancer free,” he said.

Having beaten cancer, Maxwell entered the master of engineering program at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Two years later, he interviewed for a job at NASA. He has worked in the space program ever since. He’s lived in Pasadena for 18 years, and drives a Prius when he’s on Earth.

But he wouldn’t mind leaving Earth. “You know, I still get a lump in my throat whenever an episode of Star Trek comes on television. And I love it that in human history we’re able to do things for the first time, that I can, in effect, inhabit those robot bodies and exist on another planet,” he said.

“Clearly, if there were a rocket ship leaving for Mars tomorrow I would go, never have to think about it,” Maxwell said.

Members of Maxwell’s rover team are filing daily video reports on what they’re doing athttp://www.jpl.nasa.gov/video/index.cfm?id=1133.

Maxwell is shown with a model of the Curiosity rover. (Photo courtesy Universe Today magazine)

The Curiosity rover is shown before it left Earth. (Contributed photo)