Playing Safe

ECU athletic trainers make sports safer for Pitt County high school athletes

When a North Pitt High School athlete is injured in competition, the first person rushing on the field is not the team’s coach or a worried parent. It is Jeff Barfield, a graduate assistant in health education at East Carolina University.

Barfield is one of six ECU graduate assistants who are also certified athletic trainers serving Pitt County Schools in a partnership that benefits both the community and the university.

The athletic trainers work to prevent life-threatening injuries and improve safe return to play, while helping local school systems meet requirements for a designated health care provider. At the same time, ECU gains an opportunity to enrich the students’ educations through real-world experience.

“We are pleased to be able to help support this project as it is not only good for the community, it provides valuable experience for our students,” said Dr. Glen Gilbert, dean of ECU’s College of Health and Human Performance where the athletic training program is housed.

Making athletics safer

Ron Butler, athletic director of Pitt County Schools, initiated the partnership in 2009 after he heard ECU assistant professor Dr. Sharon Rogers lecture on emergency preparedness in secondary athletic programs. Rogers now coordinates the initiative and manages the athletic trainers.

“It is now safer to compete in athletics at our high schools,” Butler said.

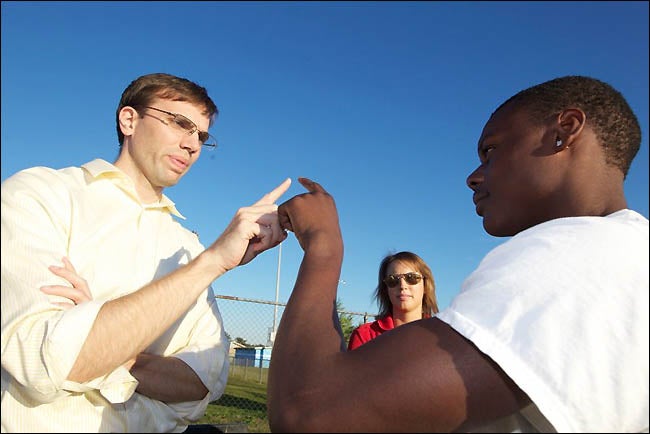

ECU graduate assistant Jeff Barfield examines an athlete’s knee before play. Barfield is a certified athletic trainer working with athletes in Pitt County Schools. (Contributed photo)

“A comparison of the care our student athletes receive now with the care they received before having these certified athletic trainers would be shocking,” said Butler. “I feel like I signed a lease for a Toyota Camry, but I am actually receiving a Rolls Royce with a chauffeur.”

The athletic trainers help the school systems meet North Carolina State Board of Education requirements that each high school designate either an athletic trainer or a first responder at all football activities. Athletic trainers are medical professionals with a 4-year undergraduate degree who have passed a national board certification exam and have state licensure. A first responder is any individual who passes a first aid and CPR course.

Dr. Brock Niceler, clinical assistant professor of family medicine at the Brody School of Medicine, is the supervising physician for the athletic trainers, who practice under his medical license. Niceler said that sports participation is an important part of adolescence because it helps teach young people about leadership, setting goals and working within a team. At the same time, athletic competition by its nature carries some risk, he said.

“Athletic trainers help minimize the risk so that athletes can enjoy the positive aspects of sports,” Niceler said. “In Pitt County, parents, athletes, athletic trainers and physicians work together to ensure the safest and quickest return to play possible.”

Niceler said athletic trainers help him do a better job because they attend practices to monitor athletes for injury and follow up daily to ensure appropriate rehabilitation.

Athletic trainers work in the patients’ environment, which decreases costs and increases the quality of health care for the athletes, he said. Niceler also sees injured Pitt County athletes in a Saturday clinic, taking advantage of information provided by the athletic trainers.

Enhancing awareness

Recent research has pointed out devastating effects when concussive injuries are mismanaged. A new state law addresses this by requiring players be taken out of activity if they may have sustained a concussion. Before the athlete can return to play, he or she must be cleared by a qualified health care provider.

Gov. Bev Perdue signed the new law this summer to promote concussion awareness in high school athletic programs. The Gfeller-Waller Concussion Act was named for two young athletes who died from concussions sustained while playing high school football. Matthew Gfeller played at R.J. Reynolds High School in Winston-Salem, and Jaquan Waller was a running back at J.H. Rose High School in Greenville.

Niceler said that 58 concussions were reported in Pitt County this fall season, from football, soccer, volleyball and cheerleading injuries. That compares to 40 concussions reported in the previous fall season.

“I don’t think we actually had more concussions. I just think we did a better job of educating and monitoring for concussions this year,” Niceler said. “This year we had mandatory coaches training as well as education for all parents and athletes about concussions. As a result, I think more athletes reported concussion symptoms,” he said.

Managing concussions

Pitt County athletic trainers cover all football activities in the fall and assist other sports’ injured athletes. In the winter season, they cover basketball and wrestling and in the spring, soccer and baseball/softball. The athletic trainers also cover practices if not scheduled to be at a home game.

Barfield, a Goldsboro native, begins his day at North Pitt High School at 3:30 p.m. His primary focus is football since it is a higher contact sport, and he has managed four football players’ concussions this season.

“Usually they come to me complaining of getting hit and feeling ‘not right,’” Barfield said. “Or if I see a hit I watch for signs of concussion. I will pull them off the field and do a series of sideline tests,” he said.

All football players completed baseline neurocognitive testing before the season began. Athletes who sustain a concussion retake the computer-based test. The scores of this post-injury test are compared to the baseline scores to help the athletic trainer and treating physician make an informed decision about the athlete’s return to play.

Becky Grant of Wisconsin, a sports management major in ECU’s Department of Kinesiology, is the athletic trainer at J.H. Rose High School. When an athlete is cleared by a physician to return to play, Grant begins a six- to seven-day progression to make sure that athlete is ready. “This consists of gradually increasing activity. If the athlete can handle the progression without the return of symptoms, then he is cleared to play,” Grant said.

Chris Hallberg of Virginia, a health education major, is the athletic trainer at Farmville Central High School.

“Having an athletic trainer at high schools is vital because otherwise many injuries would be overlooked or mismanaged,” Hallberg said.

Rogers said the presence of an ECU athletic trainer in high schools relieves untrained personnel of the responsibility for assessing potentially life-threatening conditions and more importantly, provides appropriate care and enhanced safety to athletes.

“Athletic trainers are educated and trained to help prevent injuries but also to evaluate, treat and rehabilitate the physically active when needed,” she said.

“Parents would not leave their child at a pool without a lifeguard, nor should they permit their child to engage in collision sports such as football without an athletic trainer present,” Rogers said.

###

Athletic trainers from ECU help manage safety of Pitt County high school athletes through a partnership between the university and the Pitt County school system. When not assigned to cover a game, the athletic trainers will be on hand at team practice like the afternoon practice at J.H. Rose High School pictured above. (Photo by Cliff Hollis).