ECU conservator volunteers in Haiti

Usually when Susanne Grieve works to conserve an object, it’s been at the bottom of the ocean or sound for a couple of hundred years. But for two and one-half weeks in late September, the conservator worked on restoring pieces for a culture whose artists are still alive and working.

Grieve, director of conservation for the Department of History at East Carolina University, was invited to be a part of the Smithsonian Institute’s Haitian Cultural Recovery Project, which began June 2010 and is slated to end in November. She specializes in conserving waterlogged organic archaeological materials.

Susanne Grieve

(Photo by Cliff Hollis)

The Smithsonian is leading the conservation team to help the Haitian government assess, recover and restore the country’s cultural treasures damaged by the Jan. 12, 2010 earthquake. The quake killed more than 250,000 people, left more than 1.5 million homeless and destroyed much of the country’s infrastructure. The natural disaster devastated historic buildings, museums, libraries, archives, churches, artists’ workshops and marketplaces.

Grieve worked with other volunteers in a building in Port-au-Prince that once housed a United Nations program. Intermittent electricity, crumbled buildings, and lawlessness continue in Haiti, she said. Yet Grieve said her time there changed her for the better.

“It was the most humbling experience of my life. I had never worked with local people like that before,” she said.

Grieve normally works to preserve artifacts found in maritime settings, such as parts of a ship pulled to the surface after years, sometimes centuries, underwater. In Haiti, she worked in a building without running water and often used a dry brush to take the top layer of dust and dirt off the damaged artwork or artifacts.

No art conservators were working in Haiti before the earthquake.

“The Smithsonian went in and interviewed local artists to come in and work with us as assistants (to learn how to conserve the art),” Grieve said. “The Smithsonian made a conscious effort to train and involved the locals.”

Stephanie Hornbeck, chief conservator with the Smithsonian Institution Haiti Cultural Recovery Project, said the project is now entering a transitional phase. The Smithsonian will continue to advise and support the project in some form, but the management has been turned over to the Haitian government.

During its 17 months, the project stabilized 29,000 art works, books and documents – 120 of those were deemed of high cultural importance and received advanced conservation treatment, Hornbeck said.

Artifacts and Voodoo

Grieve was impressed by the desire of the Haitian people to preserve artwork and other items of their culture, while their country struggles to rebuild the ruin left by the earthquake.

“It was my first time working where the culture and the people using and enjoying the art –and the people who made them—are still living. I think it was important for me to acknowledge that this is their culture and their heritage. And they need to decide what conservation processes go into the artwork,” Grieve said.

Hornbeck said that involving the artists from the beginning of the project was part of the Smithsonian’s plan.

“We have worked diligently and carefully to develop relationships at the Ministries of Culture and Tourism and at private and public cultural institutions. We have collaborated with our Haitian colleagues at every step in the process. Haitian professionals make all decisions regarding selecting works for treatment and giving formal permission for working with collections,” she said.

She added that the project aided more than 10 organizations with collection stabilization, storage improvements, training and treatment. And the volunteers offered nine short training workshops and more than 100 participants have participated in at least one course.

“The Haitian people are the hardest working people I’ve ever met,” Grieve said. “They are so passionate about their culture and their art. They were natural conservators, and in some cases they were better conservators than we were because they understood the material and they understood the artists’ intent, which is something we (Americans) could never comprehend, like voodoo. It’s one of the most complicated religions I’ve ever heard of.”

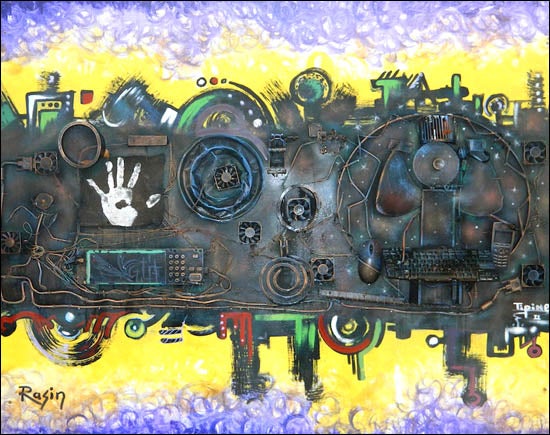

During the first of her two weeks in Haiti, Grieve worked on “some very iconic Haitian art,” called Fer Découpé, which are sculptures created from flattened steel drums. The artists cut through the steel to make the gorgeous sculptures, Grieve said.

Most of the sculptures are connected to voodoo beliefs, which are not necessary exclusive of Catholicism or Christianity, rather seen as “the practice of life and religion,” Grieve said.

Grieve worked primarily with the Lehmann Collection of voodoo objects. Swiss-born Marianne Lehmann has lived in Port-au-Prince for almost 50 years, was married to a Haitian man and worked at the Swiss embassy. Approximately 25 years ago, a voodoo priest offered to sell Lehmann a cult offering, and that piece began her extensive collection of voodoo artifacts, according to materials about her 2,500 piece collection. Lehmann evidently filled her house with artifacts and began filling another property with pieces.

“It’s all ceremonial, not touristy stuff. Every item in the collection has some sort of association with human remains. Whether it had human remains in it or portrayed. The first time I saw the collection, I left crying. Because of the overall visual of the collection, that emotional experience of seeing human remains used in ways for evil intent or good intent in some cases,” Grieve said.

“The emotional experience of knowing that some of these objects were used with evil intent is disconcerting at best,” she said.

“It was very emotional. At the beginning I was terrified. As I worked on the collection each day a little more, I almost got the sense that the objects appreciated being cared for, being cleaned. It was weird. It was almost a calming experience. It was one of the only buildings that didn’t get damaged to the same extent as the others around it in that block,” she said.

“A raw way of living”

Haiti is a beautiful, green country and their artwork reflects that, Grieve said.

“It was shocking to not only see the earthquake damage but to see what the new normal is and the living conditions that people are having to endure. The tent cities – it’s a pretty raw way of living,” she said.

“Kidnapping of American and Haitian citizens continues so we were heavily protected and guarded the entire trip. We went from the compound to the laboratory where we were working in and back each day,” Grieve said.

“I don’t think I realized the emotional effect it would have on me. I got back and I had to re-adjust to the way our society operates,” Grieve said.

Volunteers like Grieve made the project possible and effective, Hornbeck said.

Susanne Grieve is shown working on one of the Haitian sculptures created from flattened steel drums and that was damaged during the earthquake. During this part of her volunteer work, she worked in a former United Nations program building in Port-au-Prince. (Contributed photo)

“Professional volunteers from the American Institute of Conservation (AIC) like Susanne have been critical to the success of the project,” she said. The project had 42 professional conservators—experts in audio-visual materials, objects, paintings, paper and textiles—working in two-week deployments.

“The volunteers have helped with collection assessments, training, and treatment. Susanne continued treatment and supervision of two Haitian studio assistants and worked on iron sculpture and ceramics. She also joined a team to catalogue and surface-clean artifacts in an important ethnographic collection,” Hornbeck said.

The laboratories are fairly modern because of the Smithsonian’s donations to the project. “We were able to donate the tools that the local Haitians can use to continue the project, even if conservators weren’t there,” Grieve said. “A large part of my being there was training people how to preserve their artwork.”

Grieve had to shift somewhat her philosophy about the hierarchy for conservation because the Haitian people didn’t have the same attitude toward preservation priorities as Grieve would have seen in the United States.

“I had to understand that the priority that they put on the objects was what needed to be addressed and not necessarily the condition of the object. That was interesting for me to address professionally,” she said.

For example, the Haitians put higher priority on national symbols in artwork over items that might not be as culturally important but were in worse condition.

The paintings that Grieve and other conservators were working on had been punctured by falling debris, had canvases torn, or the stretcher bars had been twisted. “It was a reminder of the violence of the event,” Grieve said.

Other volunteer conservators told Grieve of being driven past some of the country’s museums and seeing walls collapsed and artwork still hanging on the walls.

“The buildings have been condemned so you can’t go in and you know there’s artwork that’s out in the sun and the rain. All of the artwork, even the ones we treated, were out in the elements for about a month before they were recovered,” she said.

Another gruesome reminder of the enormity of the earthquake was the layer of concrete dust everywhere, Grieve said. One of the assistants told Grieve that before the earthquake the Haitians didn’t use the word for “debris” in their vocabulary.

Hornbeck said the Smithsonian Institution Cultural Recovery Project made a positive impact on Haiti and the preservation of damaged cultural artifacts. She heard from others that representatives from other groups came and toured the devastation and promised help, the Smithsonian was the only one to establish a serious project.

“Our project has been very positively received in Haiti. While it has a venerable tradition of artistic creativity, Haiti does not have an established infrastructure for preservation of its patrimony. So, our project aimed to both provide needed expert assistance and to introduce conservation concepts and practices,” Hornbeck said.

Grieve said even though the project conserved thousands of items, thousands more remain so she hopes the funding can be secured for the project can continue in some form.

“I’m glad that I got to participate in the project since it is coming to a close and extremely grateful to have met the Haitian people and really understand their plight,” Grieve said. “Every day was a reminder of how raw life is in Haiti.”

# # #

A piece of artwork from Haiti is shown after conservation through the Smithsonian Institute’s Haitian Cultural Recovery Project. (Contributed photo)