Oil and water don’t mix

Scientists study how far up the food chain oil from the Deepwater Horizon spill will go

Off Onslow Bay, a group of East Carolina University researchers have been looking for oil.

But unlike most in this world of $90-a-barrel crude, they aren’t hoping to find a gusher of Texas tea. In fact, they hope to see nothing but salt water.

Sailing into the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean, a number of ECU scientists are piecing together clues to determine what effects the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill had on the Gulf and its sea life as well as whether that oil has made its way to the North Carolina coast.

“One of the concerns with this spill is that it vanished so quickly,” said Dr. David Kimmel, an assistant professor in the department of biology and the Institute for Coastal Science and Policy at ECU. “We all know…4.9 million barrels is a tremendous amount of oil, so the question is where did it go?”

The answers could be valuable for advancing the technology of oil spill cleanups as well as setting a baseline of oil presence for the North Carolina coast in case a future spill does reach the area.

Building on prior research

Last summer, Kimmel and a team of researchers spent several days on the Gulf of Mexico using devices such as a laser optical plankton counter and other methods to assess the number, condition and migration patterns of zooplankton and other sea life. The findings help determine the oil spill’s impact on the ocean ecosystem.

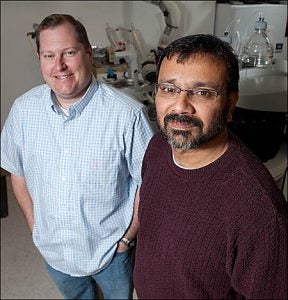

Drs. David Kimmel, left, and Siddhartha Mitra are studying the effects of oil on the ocean food chain. (Photo by Cliff Hollis)

Funded by the National Science Foundation, Kimmel is studying the tiny animals that act as a direct link between two levels of the food web: the primary producers, phytoplankton, similar to plants on land that fix carbon, and upper level organisms, such as fish, that are consumed by humans.

Kimmel’s grant is a collaboration with colleagues at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Sciences and Oregon State University. Between 2003 and 2009, they conducted five summer cruises in the northern Gulf of Mexico to collect and analyze samples.

“Thus, we possessed an extremely valuable dataset to compare the possible effects of the BP oil spill on the ecosystem of the gulf,” Kimmel said. Specifically, Kimmel is working to determine if the spill has altered the distribution of plankton, important organisms that form the base of the food chain. According to Kimmel, an alteration of plankton distribution or abundance could dramatically impact fisheries production in the gulf.

Dr. Siddhartha Mitra’s organic geochemistry lab is “fingerprinting” some of the organic compounds that are associated with the oil from the BP spill. That fingerprint is necessary in order to proceed with further research or natural resource damage assessments that might hold BP liable.

Following last year’s oil spill, Mitra took rainwater samples in the gulf and water and sediment samples off the N.C. coast. He’s also been working with zooplankton Kimmel and his team collected. Analysis is showing the BP oil fingerprint in zooplankton tissue. Their group is working on articles that document that analysis and expect to publish them this year.

Mitra and scientists and staff at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington are determining background levels of hydrocarbons in water samples from coastal North Carolina. This information would be important if an oil spill from elsewhere did make its way to the N.C. coast.

Though Kimmel and Mitra have separate NSF RAPID awards, during the past few months they have begun collaborating to look for the presence of that hydrocarbon signature within zooplankton from the Gulf of Mexico. Their preliminary results suggest that zooplankton in the gulf have been impacted by the oil spill. Zooplankton collected from the gulf last August and September contain chemicals that can be traced directly to the BP spill using Mitra’s fingerprinting methods.

This finding is important because certain chemicals that make up oil might accumulate within the food web, potentially presenting a threat to humans who consume these fish.

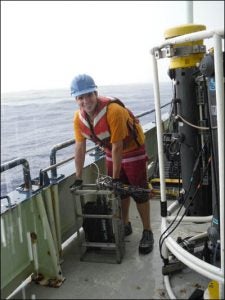

Graduate student Ben McGlaughon prepares to deploy a laser optical plankton counter last summer on the Gulf of Mexico. (Contributed photo)

Some speculate that oil exploration off the coast of North Carolina is imminent. That is why Kimmel and Mitra, with $4,900 in funding from N.C. Sea Grant, are sampling water and zooplankton to determine water quality and the health of the ecosystem. Such information is critical to have before any drilling begins off the Carolina coast.

Kimmel and Mitra aren’t the only ECU researchers studying oil. Drs. Ed Stellwag, Anthony Overton, Xiaoping Pan and Baohong Zhang of the ECU biology department also received a one-year NSF grant for $199,477 to study the influence of crude oil exposure on genetic mechanisms of fish development.

In the field and lab, researchers have looked at the developmental effects of exposure to dispersant-treated crude oil. They are using next-generation DNA sequencing technologies and bioinformatics analysis methods to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the developmental defects related to crude oil exposure.

They hope their results will be useful in establishing measures to mitigate the damaging effects of environmental pollutants on this sensitive stage of life.

A ‘natural’ partnership

Mitra said the collaboration across departments – geology and biology in the case of Kimmel and himself – has worked well.

“It’s very natural because we’re both trained as marine scientists,” he said, adding they each trained on the Chesapeake Bay.

They are also giving students a close-up look at field research. Graduate student Ben McGlaughon worked around the clock on the gulf collecting samples. Working at sea presented a lot of challenges and opportunities for creative solutions. It also helped him focus on career goals.

“Being involved with research on one of the worst environmental disasters in human history really helped me realize that these are the kinds of issues I want to be sure we can avoid in the future,” McGlaughon said.

On the gulf today, the water has that certain blue sparkle. Less certain – to scientists and students alike – is where 4.9 million barrels of oil went.

“I’m not entirely sure what happened to the oil in the gulf,” McGlaughon said. “I believe it definitely made its way into the system, most likely as a combination of uptake by zooplankton and other marine organisms and through sedimentation into the seafloor. I think a lot of people are taking an ‘out of sight, out of mind’ opinion regarding the gulf oil, which I don’t think is a great mindset to have.”

###