Doctoring is a family tradition for the Joneses

A career spent working as a family doctor, teaching medical students and supporting the medical school at East Carolina University was recognized Friday at ECU’s new Family Medicine Center.

Dr. Robert S. Jones, who for more than 50 years practiced medicine in Shelby, was named affiliated professor emeritus, a title that reflects his years of service to the school and its students. His sons, Drs. Robert Jones Jr. and Stephen Jones, are ECU medical graduates and still practice in their hometown.

Seeing a need in the East

Jones was an early supporter of building a medical school at East Carolina. His sister had married a physician who practiced in the northeastern North Carolina town of Ahoskie. Thus, Jones got a close look at the lack of medical services in the east. The sick and injured had to travel to Raleigh, Norfolk or Richmond to receive advanced care, and he knew that needed to change.

“Time means a lot when you’re very sick,” he said.

He believed enough in the new school in Greenville that his son, Robert Jr., enrolled in 1977 with the first class of four-year students. His youngest son, Stephen, graduated from ECU’s medical school in 1986 and stayed to complete his residency training in family medicine.

“We feel like they got as good a medical education as was available,” the father said.

When ECU decided it needed to build a new Family Medicine Center, Robert Jones’ donation was the first the university received to help build it and reflected his belief in the importance of a strong family medicine program.

“That’s the basis of all of it,” he said. “It starts with family practice.”

In total, he and his sons have given nearly $40,000 to help build the center. In recognition of that, the outside of the Chair’s Conference Room at the center bears a plaque commemorating the family’s support.

Dr. Kenneth Steinweg, chair of family medicine at ECU, talks with Dr. Robert Jones and his wife, Mabel. Photo by Cliff Hollis

Perhaps as important as the financial contributions have been the contributions in time and knowledge to the students who, since 1985, have rotated through the Shelby practice on their way to a medical degree.

“I would have given anything when I was coming along to have an opportunity to go into a doctor’s office for a few weeks,” Robert Jones said.

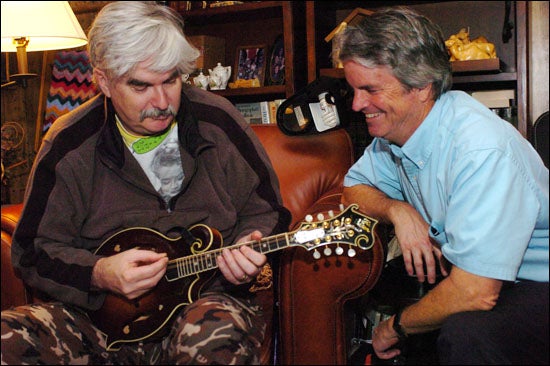

While Stephen Jones, his father, mother and wife were at ECU, Bobby Jones was back home in Shelby, unable to make the trip. A musician, songwriter and author in his spare time, he let his music do the talking earlier this year when he found out he had brain cancer.

“I’ve got the brain tumor blues, but that don’t mean I’m through,” goes the beginning of a song he wrote. “My neurosurgery pal drilled a hole in my skull and did what he could do.”

At his home in August, he recalled how that first class felt an obligation to make good on the support of the lawmakers and others who created it.

“We had a microscope on us,” he said. “Everybody knew if we didn’t do well on boards we had wrecked a major undertaking.” The students succeeded, in part due to their patients.

“A lot of the patients had not had great access to care prior to East Carolina,” said Stephen Jones. “So the spectrum of illnesses we got to see as medical students and residents, I think the training was as good as we could have gotten anywhere in the country. It was a really, really good fit for me. It was the right spot for me.”

Following the footsteps

After medical school, the Joneses joined their father’s practice. It was a typical small-town practice, where the doctors knew many of their patients personally. Bobby Jones would later branch out on his own.

Though their father, 86, recently retired, his lessons still shape their practices. One example was years ago, when they were boys and on a camping trip at Lake James with their father and some friends. A game warden sought them out and told Jones a woman back in Shelby was in labor and wanted him to deliver her baby. Jones left his boys with the others, went into town, delivered the child, then returned to the campsite about 4 a.m.

“She wanted him, and that’s the service we try to provide, that real personal service,” Stephen Jones said.

Their mother, Mabel, also had a role in encouraging her sons to be scholars. “Every week, I took our children to the library,” she said. They had a third son, Henry, between Bobby and Stephen, who became a high school English teacher. They would read their books, then go back the next week to return them and get new ones.

“Bobby told me that was one of the greatest things I did for them growing up.”

No matter how smart a physician is, however, today, regulations, paperwork and the cost of electronic medical records systems make it hard for independent practices to generate enough revenue to offset costs. Shelby is now down to three independent practitioners in primary care, including Stephen Jones’ three-doctor practice. Other practices, including his brother’s, have joined with hospitals.

“I guess I’m just hard-headed,” Stephen Jones said. “I don’t think it’s in the best interest of the patients for medicine to become monopolized and limit choices where patients can go. It’s a shame someone can’t come out of med school and set up their own practice. I think those days are done.”

He does more, however, than see patients in the modest two-story building near the Shelby hospital. On the second floor is a thriving clinical trials operation, where staff members evaluate the progress of patients being treated with experimental drugs.

“The FDA wants real-world. They don’t just want academic settings,” Jones said.

While his brother plays mandolin and writes, Jones calls himself more of an “adrenalin junkie.” He is a barefoot water-skier who flies helicopters and airplanes – as does his father, who still has his pilot license. The family flew to Greenville in Robert Jones’ Cessna 310.

Fight the cancer, not the system

Stephen Jones also believes his brother has a good chance against his cancer. “He’s a tough guy. He’s doing real well,” he said.

In August, Bobby Jones talked about finding out that his sudden vision problems were caused by a tumor. “When a doctor tells you he’s disappointed you didn’t have a stroke, that’s a pretty bad sign,” he said. “The bad news is it’s an area of the brain that’s very difficult to operate on.”

Radiation and chemotherapy treatments, however, are showing results. Jones has progressed enough that he’s back at work part-time, seeing patients in an advisory role. A new grandchild came into the world Oct. 13, he’s playing his mandolin and he’s working on projects such as a children’s coloring book that has music lessons thrown in. But he felt like the trip to Greenville for Friday’s event would wear him down for several days.

He said his experience as a physician has helped now that he’s on the other side of the stethoscope.

“The insight you have helps when it hits,” Jones said. “You don’t have to overpower the experts. You have to make the system your friend. Play a song for them and try to make their day a little brighter.”

###