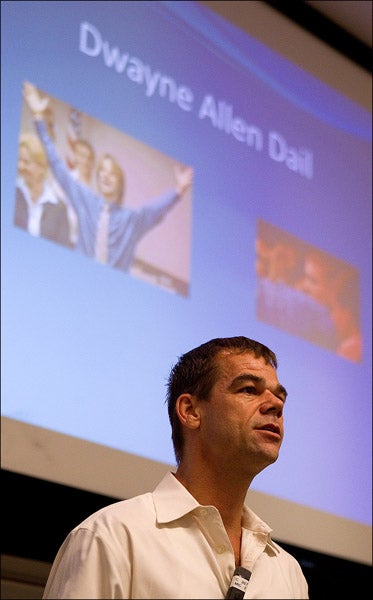

RIGHTING A WRONG

Exonerated prisoner Dwayne Dail shares his story with Pirate Read audience

If Dwayne Dail can help prevent just one person from being wrongly accused and convicted of a crime, it will be worth it, he said.

On Sept. 27, Dail told East Carolina University students about being charged, convicted and sentenced to two life sentences for the rape of a 12-year-old Goldsboro girl in 1989. He was exonerated in 2007 through DNA testing on crime scene evidence that was thought to have been destroyed but later found through the efforts of Christine Mumma and the N.C. Center on Actual Innocence. The center is a nationally-recognized non-profit organization which examines innocence claims by convicted felons in North Carolina.

Dail and Mumma’s visit to ECU was in connection with the Pirate Summer Read, “Picking Cotton: Our Memoir of Injustice and Redemption,” a book about how two people’s lives became intertwined through a case of misidentification and a prison sentence that followed.

Christine Mumma

First-year students were asked to read the book before the fall semester began. “Picking Cotton” was written by rape survivor Jennifer Thompson-Cannino and the man she mistakenly identified as her rapist, Ronald Cotton, and co-authored by Erin Torneo. Cotton was exonerated after 10 years in prison through DNA testing. The book and related topics are being discussed in courses and events across campus, including a visit by the authors Oct. 4.

Statistics show that 75 percent of people are wrongfully convicted because of misidentification and, of those, 40 percent involve victims and alleged perpetrators of different races. Both played a part in Cotton and Dail’s cases. Cotton is black; Jennifer Thompson-Cannino is white. Dail is white; the little girl in his case was black.

Mumma said that the man who actually raped Thompson-Cannino was brought to Cotton’s second trial. Convinced that Cotton did it, Thompson-Cannino told authorities that she had never seen the other man before in her life.

Often when a victim identifies a suspect, investigators zero in on that person, what Mumma calls “tunnel vision,” which can lead law enforcement away from the actual offender. Other causes behind faulty convictions are false confessions, snitch testimony, misconduct or, what Mumma believes is the biggest, ineffective counsel. It’s a “human house of cards,” Mumma said. “The term ‘human error’ exists for a reason.”

Changes are needed in evidence collection, maintenance and preservation, Mumma said. The center also is pushing for recordings of interrogations. Part of the center’s mission is educating policymakers, students, the public, the media and the legal and law enforcement communities about systemic problems in the criminal justice system that lead to wrongful convictions, and finding solutions to those problems.

Finding justice

For Dail, Mumma’s involvement in his case was a lifesaver. He spent 6,725 days in prison for a crime he didn’t commit. He never had been in trouble with the law before he was convicted.

“The things that happened to him in prison were very difficult,” Mumma said. “Everyone knew he was in as a child rapist. For 18 years, he suffered the consequences of that information.”

Dail said he was not “street smart,” and absolutely terrified at going to prison. “I was clueless to the rules, and I learned them all the hard way,” he said. He was transferred to 16 different institutions in his 18 years behind bars. His family and friends did everything they could by writing letters, following DNA cases across the country and trying to get DNA testing multiple times.

A prison psychologist believed in Dail, and put him in touch with Richard Rosen, professor emeritus at the UNC School of Law, who put him in contact with the Center on Actual Innocence. The center coordinates the Innocence Project at each of North Carolina’s law schools, part of a national network, and law students volunteer on casework.

The rape kit in Dail’s case was destroyed in 1994. For years, he was told there was no evidence that existed to do DNA testing. But officials were wrong. The girl’s nightgown and bed sheets from the crime were bagged and misplaced. The items were not inventoried and remained there for years. The evidence showed another man, William Neal, who lived near the little girl actually committed the crime and he was later convicted and sentenced.

Dail had the opportunity to meet his accuser during Neal’s trial. He places no blame on her. “She was a 12-year-old raped at knifepoint. She bears no responsibility for that,” said Dail, adding the Goldsboro Police Department did not fully investigate the crime.

Telling his story

Dail spoke publicly many times after his release, but has struggled since being freed. The presentation at ECU was the first time he had shared his story in almost two years, Mumma said. “The more he was living in the past, the more difficult it was,” she said.

“People think my troubles ended in 2007,” Dail said. “But a whole new set of troubles began.”

Meredith Shaw, a senior and ECU Pre-Law Society member from Wake Forest, said meeting Dail was something she will never forget. She had researched Dail’s case before his visit because she would like to work for the Innocence Project one day.

“Hearing his story from his point of view really helped put my law pathway into perspective for me,” Shaw said.

“Picking Cotton” was inspirational, Shaw said, because of the relationship that formed from a terrible event. “It goes to show that mistakes do happen, and there is a time to forgive no matter how bad the situation was,” Shaw said.

Rebekah Currie, a freshman from Tarboro, said she loved the book and empathized with the characters. Mumma and Dail’s presentation gave her a better understanding of the legal system.

“There are way more innocent people in prison than I thought,” she said. “I knew there were probably some, but after reading ‘Picking Cotton’ and seeing the presentation, it opened my eyes to how unfair our justice system can be.”

Currently the N.C. Center on Actual Innocence has 58 active cases, but receives thousands of inmate inquiries each year. Most come from guilty people, Mumma said.

“Most convictions are reliable and correct,” she said. “But there are absolutely some innocent people in prison. There are absolutely some innocent people who will die there, and Dwayne came awfully close.”

Across the country, DNA evidence has helped exonerate 273 wrongfully convicted prisoners. Seventeen were on death row. “Dwayne was 207,” Mumma said.

For a link to Mumma’s presentation at ECU, go to www.ecu.edu/fyc. For more information on the N.C. Center on Actual Innocence, visit www.nccai.org.

###