Students find secrets in sand at Fort Macon

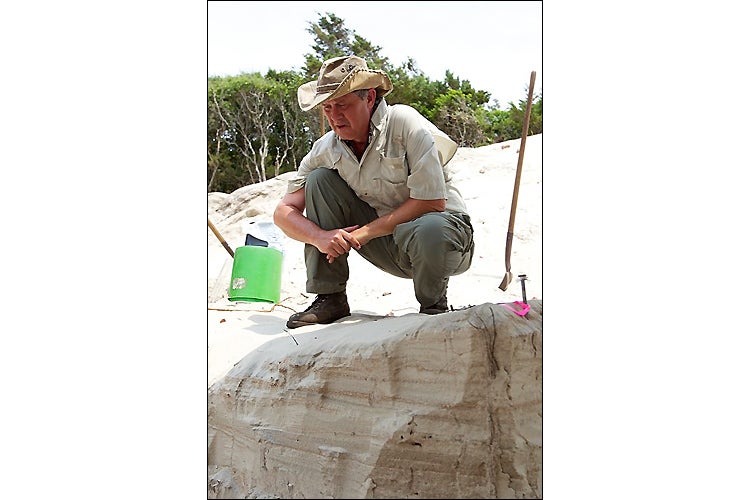

Students from East Carolina University wrapped up an archaeology dig at Fort Macon State Park last week that should help shed some light on what life was like for Civil War officers and their families.

Nearly a dozen students spent their first summer session unearthing the remains of the home of Lt. William Eliason, who led the Army Corps of Engineers group that built the fort from 1826-1834. State officials wanted the location of the home studied as part of an educational program on the 150th anniversary of the Civil War siege of the fort in 1862.

Fort Macon was built as part of a chain of forts that would protect Atlantic coast of the United States from sea attacks and invasions. The five-sided fort cost $463,790.

At the beginning of the Civil War, North Carolina seized the fort from Union forces, which consisted of a single ordnance sergeant. Union forces attacked and took over the fort in 1862; the Confederates burned down the Eliason house before the Union siege. For the duration of the war, the fort was a coaling station for navy ships, and the area around it was largely desolate.

“Back then, it really was the end of the world, or at least you could see it from there,” said Dr. Charles Ewen, the professor of anthropology who’s leading the dig.

The federal government abandoned Fort Macon in 1903, and the state acquired it for $1 in 1924. After restoration work by the Civilian Conservation Corps, the fort opened in 1936 as North Carolina’s first functioning state park.

Troops were stationed at the fort during World War II, and though the fort didn’t see action, a German submarine was sunk just off the coast. Following the war, the fort again became a state park. More than 1 million visitors walk its grounds every year, making it one of the state’s most visited parks. In recent weeks, several visitors have wandered over to the dig site to see what was going on.

Since May, the students have found artifacts ranging from a brass folding comb to a 32-pound cannonball. They’ve also found numerous bits of lead shot, including one ball that an apparently bored serviceman carved into a bishop for a chess set.

The course is a combined undergraduate- and graduate-level field school, anthropology 3175 and 5175, field methods/advanced field methods in archaeology. From morning until late afternoon, students skim sand with shovels, empty them into 5-gallon buckets, empty the buckets into sifters, then slide the sifters back and forth to screen for artifacts.

“It opens your eyes about whether you want to do it or you don’t want to do it,” said Mary Katherine Pope, a senior from Nashville, Tenn., as she took a break from sifting sand. “I like it. I like getting my hands dirty.”

The house was a two-story frame structure with a cellar and two full porches overlooking the ocean, about a quarter-mile away. The house was believed to have had a wooden basement floor, but the students discovered a brick floor, possibly installed after the planks deteriorated.

Graduate student Kyle McCandless found the cannonball in the basement. He’s worked at sites in Old Salem and Greece and hopes to teach at a community college. He likes connecting with the past, but wouldn’t necessarily want to live in it – at least not at Fort Macon in the 1800s.

“If I were a wealthy person living in the house, sure,” he said between shovel scoops. “If I were part of the military, maybe not as much.”

Graduate student Valerie Robbins of Cary will base her master’s thesis on the Fort Macon dig. She said the residence was likely a nice home, but digging out its remains isn’t so nice. “It’s hard labor. It’s work,” she said. “It’s not like the movies. It’s shoveling.”

Robbins, who’s also done field work in England, will present her research at the Society for Historic Archeology annual meeting in Baltimore in January.