ECU biologist finds proof of the first monogamous frog

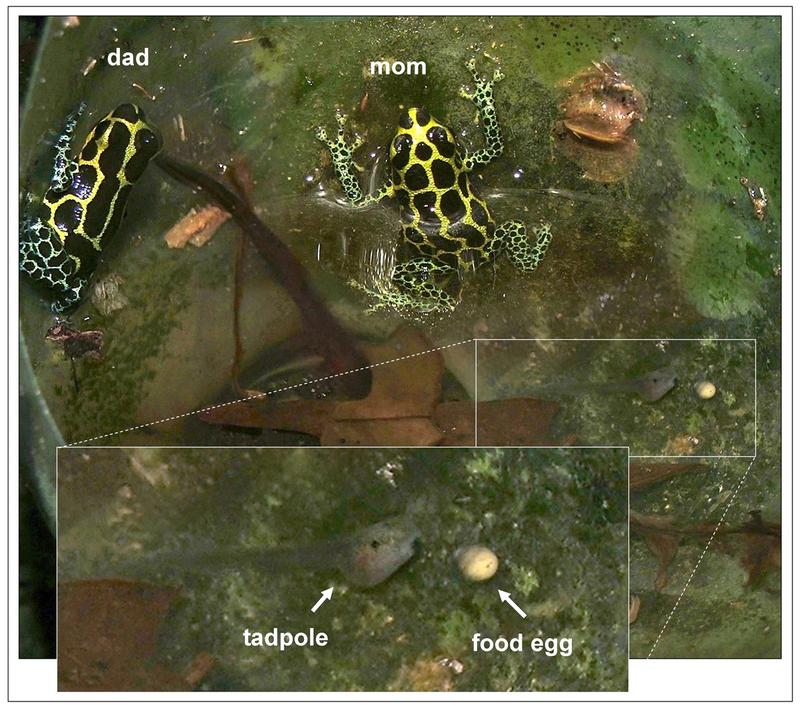

This photo shows a “family” of Ranitomeya imitator amphibians, better known as mimic poison frogs. Photos courtesy of Jason Brown.

GREENVILLE, NC — Amphibians may be a love ’em and leave ’em class, but one frog species defies the norm, scientists have found.

A trio of biologists, including two from East Carolina University, have discovered in Peru the first confirmed species of monogamous amphibian, Ranitomeya imitator, better known as the mimic poison frog — a finding that provides groundbreaking insight into the ecological factors that influence mating behavior.

The scientists’ work, which is to be published in the April issue of The American Naturalist, may be the most solid evidence yet that monogamy can have a single ecological cause.

“We were able to tie the evolution of monogamy and the evolution of biparental care to variation in a single ecological factor, and that’s rare,” said Kyle Summers, an ECU biology professor whose specialties include evolutionary ecology and evolutionary genetics. Summers authored the study with Jason L. Brown, a former ECU graduate student now a researcher at Duke University, and Victor Morales of Ricardo Palma University in Lima, Peru.

Analyzing data on 404 frog species, the biologists found a strong association between the use of small pools for breeding, and the evolution of parental care, including intensive parental care involving egg-feeding and the participation of both parents. The researchers then focused in on the mating and parenting habits of two similar frog species, the mimic poison frog and the R. variabilis, more commonly known as the variable poison frog, that differed mainly in the size of the breeding-pool.

They theorized that the differences in parental care and mating system between these otherwise similar species stemmed from the relative availability of resources in the breeding pools. The tadpole of the mimic poison frog grows up in much smaller, less nutrient-dense water pools that form in the folds of tree leaves. They are ferried there after hatching by males, who monitor them in the months following birth. About once a week, the male calls for his female partner, who lays non-fertile eggs for the tadpoles to eat.

The variable poison frog, however, raises its tadpoles in larger pools. Here, as with most amphibians, rearing of the young is handled mostly by the male.

To test their theory, scientists moved tadpoles from both species into differently sized pools. Tadpoles in larger pools thrived while tadpoles in smaller pools did not grow.

This, the scientists said, means that tadpoles living in the larger, more nutrient-rich pools don’t need the work of two parents as much as their smaller-pond counterparts. Species that raised tadpoles in smaller ponds were more likely to require the skills of both parents. In turn, this likely favored parents who remained devoted only to the offspring that they had produced together.

The researchers used genetic analyses based on techniques similar to the DNA-based forensic methods used for paternity cases to investigate the mating system of the mimic poison frog. Surprisingly, the all but one of the families investigated were completely genetically monogamous. Many animals thought to practice social monogamy have been found through genetic testing to be less faithful than previously believed. Monogamy “turns out to be relatively rare, eve in birds and mammals — particularly in mammals — and reptiles,” Summers said. “Finding a frog that has a monogamous mating system was pretty novel for us.”

The biologists’ work already has attracted attention from scientific and popular media, both international and national. While the idea that ecological factors — say, scarcity of resources — have contributed to monogamous behavior in humans and other animals is well accepted, Summers cautioned against drawing inferences about human behavior from the findings.

“People are interested in whether there are parallels between mating systems of other species and our own,” he said. “Of course, the human situation is so different from other species. It’s somewhat perilous to over interpret the similarities. You can’t just translate it.”

This mimic poison frog carries a tadpole on its back.